Introduction

It started with something that looked almost harmless, a tiny math mistake deep inside the code of a DeFi platform called Balancer. Yet that small rounding error grew into one of the biggest decentralized finance losses of 2025. In early November, attackers found a way to take advantage of the bug, draining over $100 million worth of tokens across several chains in just a few hours.

This event showed how even a single decimal point error in blockchain systems can cause massive damage. The Balancer exploit was not caused by a traditional security flaw like a stolen key or broken access control. Instead, it came from how computers handle numbers, especially when working with large sums of digital money.

Understanding this incident matters because many other DeFi platforms use similar math libraries and face the same risks. The story of the Balancer exploit teaches one clear lesson: small precision errors can have very big consequences.

Background and Context

Balancer is a decentralized exchange (DEX) that lets users trade tokens and provide liquidity through automated pools. These pools are powered by mathematical formulas called invariants that keep the pool balanced between its tokens. One special type of Balancer pool, the Composable Stable Pool, is designed for stablecoins and similar tokens that have almost equal values (like USDC and DAI).

To keep prices stable, these pools use fixed-point arithmetic, a way of handling numbers without decimals on the Ethereum blockchain, since Ethereum doesn’t support floating-point math. Instead of storing “1.23,” the system stores “1230000000000000000” (that’s 1.23 multiplied by 10¹⁸). This technique works well but requires careful rounding.

In Balancer’s case, the rounding rules were too aggressive; they always rounded downward. This may seem tiny, but each trade caused the pool’s internal balance formula to lose a fraction of value. When repeated thousands of times, these “lost crumbs” added up to real money.

Attackers realized that if they performed many small swaps in a certain order, they could force the pool to keep rounding in their favor. Each small trade pushed the math slightly off, and after many such trades, they withdrew tokens worth far more than they put in.

This issue was part of the Balancer V2 codebase, affecting pools that shared the same stable-pool math library. Since Balancer pools exist across several blockchains (like Ethereum, Arbitrum, and Polygon), the impact spread quickly.

By November 3–4, 2025, on-chain analysts noticed unusual activity, tiny repeated swaps followed by large withdrawals. Within hours, it became clear that a rounding bias in the math code had been turned into a multi-chain exploit.

Hypothetical Scenario

Imagine a shop that uses a cash register that rounds down every price to the nearest whole number.

If something costs $10.99, the register records it as $10. You wouldn’t notice much if it happened once, but now imagine a clever shopper who buys hundreds of items at $10.99 each. Every time, they save $0.99 without anyone noticing. After 1,000 items, that small difference turns into nearly $1,000 in free goods.

That’s exactly what happened with Balancer. The “register” (its pool math) kept rounding down tiny amounts. The “shopper” (the attacker) found a way to repeat this rounding over and over again, then “checked out” with the profits.

Vulnerability Description

The Balancer exploit began from a very small but powerful mathematical mistake. Inside Balancer’s stable pool code, a rounding error quietly shifted the value each time a trade occurred. Because Ethereum does not use decimal numbers, all amounts are stored as large whole numbers. For example, instead of storing 1.23, the blockchain stores 1230000000000000000. Every calculation involving division or multiplication must round the result to a whole number.

Balancer’s code always rounded numbers down when calculating pool balances. Each time a user traded, the pool lost a tiny fraction due to this rounding. Normally, this was too small for anyone to notice, but an attacker studied the math carefully and found that the rounding happened in a way that could be repeated for profit.

To understand this clearly, imagine the pool has two tokens, Token A and Token B, both worth about the same. Balancer keeps a special number, called D, that helps maintain the balance between these tokens. When someone swaps A for B, Balancer recalculates D using fixed-point math, and that calculation involves rounding down.

Here’s what the attacker did: they made very small trades back and forth between Token A and Token B. For example, they swapped 1 unit of A for B and got 0.99 B because of rounding down. Then, they immediately swapped that 0.99 B back to A. Due to how the rounding worked inside the pool, they now ended up with 1.001 A. That tiny gain of 0.001 A is a profit. One round of trading gave almost nothing, but by repeating this pattern many times, the attacker kept collecting small gains that added up.

An ordinary user might lose a fraction of a token from rounding, but the attacker used the system against itself. By performing thousands of these small swaps, often in a single large transaction, they made sure that every rounding favored them. They did this across many pools and even across multiple blockchains where Balancer’s same pool code was deployed.

Attackers also used flash loans to make this attack bigger. A flash loan allows someone to borrow large amounts of cryptocurrency in one transaction and repay it at the end. The attacker borrowed millions, ran thousands of tiny profitable swaps inside that single transaction, and then repaid the loan, keeping the profit.

Imagine if each tiny cycle gave a gain of only 0.001 token. If one token is worth $1,000, that is $1 per cycle. Ten thousand such profitable cycles equal $10,000 in profit from one pool. If the attacker repeats this across multiple large pools filled with millions in liquidity, the total can reach tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars.

This rounding bug was not a normal “hack” where someone breaks into a system or steals keys. It was a logical exploit, a way to profit from how the system itself was designed to do math. The attacker didn’t bypass any permissions or security layers. They simply understood the math better than anyone else and used it repeatedly to shift value in their favor.

By the time the issue was discovered, the same rounding error had been exploited across several pools and chains. Each tiny arithmetic bias that seemed harmless in isolation became devastating when executed in thousands of small steps. What looked like a simple decimal problem ended up draining more than a hundred million dollars in value from Balancer’s ecosystem.

Impact and Scope

The Scale of the Loss

The Balancer exploit wasn’t a small glitch; it was one of the biggest decentralized finance (DeFi) losses of 2025. By the time it was discovered, over $100 million worth of tokens had been drained from Balancer’s stable pools across multiple blockchains.

It started with a few suspicious trades on Ethereum, but soon spread to other networks where the same vulnerable Balancer code was deployed on Arbitrum, Base, Polygon, and even some Balancer forks. Because these pools all shared the same math library, the bug repeated everywhere, just like a software virus spreading across identical systems.

Who and What Was Affected

The victims were mostly liquidity providers (LPs), ordinary users, and DeFi projects who had locked their tokens inside Balancer pools to earn fees. These users didn’t lose access to their wallets, but the value of their pooled tokens dropped sharply because the pool itself was drained.

The most affected assets were WETH, stETH, osETH, and other liquid staking tokens, which are popular in Balancer’s stable pools. Each token pair that relied on the same vulnerable “stable math” suffered losses.

Balancer’s version 2 (V2) pools were directly impacted, while version 3 (V3) pools built with a newer math library were not affected.

Multi-Chain Ripple Effect

Because Balancer operates on several networks, the attack’s effect was like a domino chain:

● On Ethereum, early pools were drained first.

● On Arbitrum and Base, attackers used the same technique only minutes later.

● On Polygon and other Balancer forks, cloned versions of the code faced similar drains.

This showed how shared smart contract libraries, while efficient, can multiply the damage of a single flaw across multiple ecosystems.

Economic and Community Impact

● Liquidity collapse: Once the exploit was confirmed, users rushed to withdraw funds from other pools, leading to sharp liquidity drops.

● Price shocks: Tokens in affected pools temporarily lost their peg (value balance) because the pool math no longer reflected real prices.

● Loss of confidence: Even users not directly affected lost trust in DeFi safety. Many projects using Balancer’s code paused or limited their operations.

● Operational disruption: Exchanges, aggregators, and DeFi dashboards relying on Balancer pools had to shut down or filter out affected data.

The Broader Lesson

This wasn’t just a Balancer problem; it was a wake-up call for the entire DeFi ecosystem. It showed that:

1. Smart contract math bugs can be as dangerous as logic bugs.

2. Code reuse spreads risk if one core library fails, every project that depends on it can be exposed.

3. Financial systems need runtime monitoring, not just audits.

Static Analysis

This pool family performs all pricing and accounting in 18-decimal fixed point, using helper libraries that enforce exact rounding modes. Amounts are first converted from token decimals to 18 decimals, then passed into the stable-invariant solver, and finally converted back. At each stage, the code applies deterministic rounding. The combination of early floor rounding, repeated floor divisions in the solver, and a hardcoded plus or minus one adjustment at the end of swap calculations creates a small one-way bias. A single swap shows a dust-level effect. Repeating many small swaps or chaining micro-swaps in a batch can accumulate that dust into value.

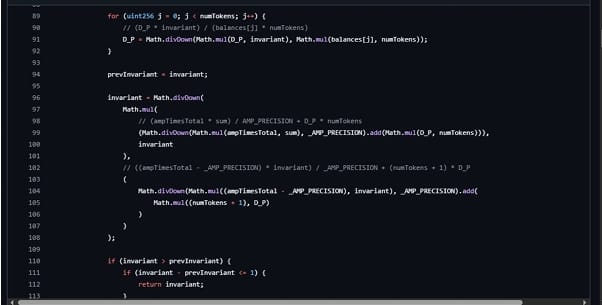

The core math is in StableMath.sol. The main invariant function is _calculateInvariant.

It computes the stable pool invariant with Newton iterations and uses Math.divDown multiple times per iteration. The function stops when the change is less than or equal to one unit at the 1e18 scale. This design fixes the rounding direction to floor for most intermediate results and accepts a coarse absolute tolerance.

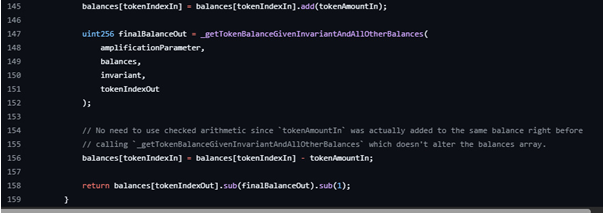

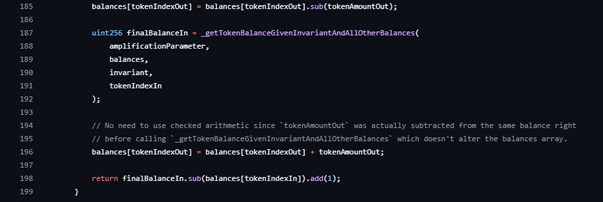

The swap calculators _calcOutGivenIn and _calcInGivenOut both mutate balances, call the inner balance solver, and then force an extra one-unit nudge on the returned amount. _calcOutGivenIn subtracts one from the computed amount out. _calcInGivenOut adds one to the computed amount in.

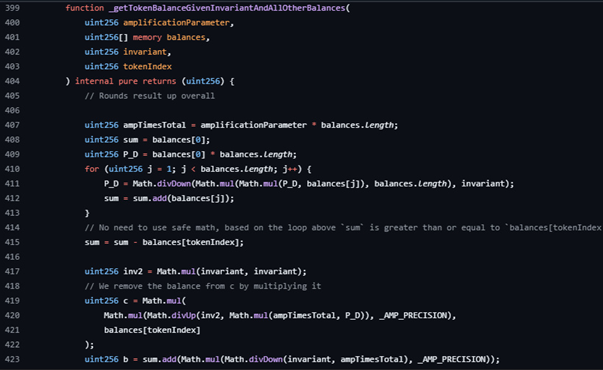

The inner balance solver _getTokenBalanceGivenInvariantAndAllOtherBalances mixes up-round and down-round on separate sub-expressions and uses a Newton step that rounds up, with the same absolute one-unit stop rule. Taken together, the library is not neutral. It encodes a consistent rounding direction at each step and applies a fixed ±1 adjustment on the final result of each swap calculation.

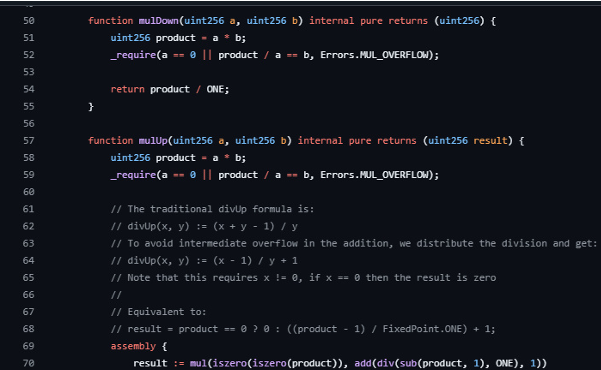

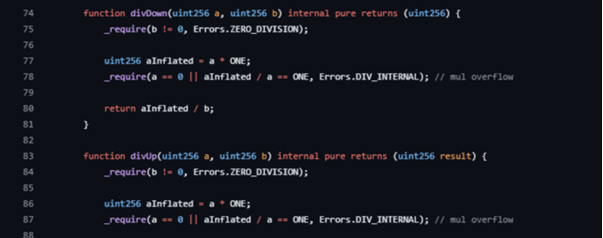

The rounding rules come from FixedPoint.sol and Math.sol. FixedPoint.mulDown and FixedPoint.divDown always floor. FixedPoint.mulUp and FixedPoint.divUp always ceil.

Math.divDown and Math.divUp do the same for plain integers. These helpers are used everywhere in StableMath.sol, so their behavior defines the direction of every remainder. Because the code performs several divides per iteration in _calculateInvariant and per step in the token-balance solver, any remainder is thrown away in a consistent direction. If the final result is then pushed by an extra unit, a predictable bias remains.

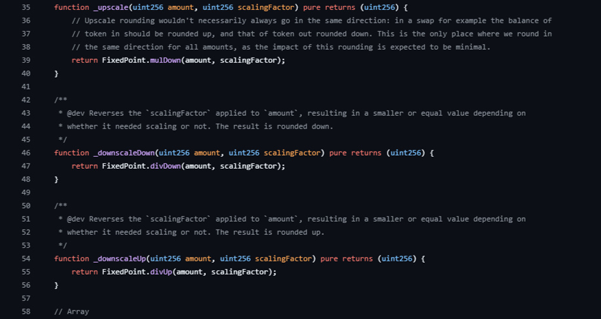

Before and after the solver, amounts pass through the scaling layer in scalinghelper.sol. _upscale and _upscaleArray convert token amounts to 18-decimals using FixedPoint.mulDown. That is an early floor rounding. _downscaleDown floors the result when converting back. _downscaleUp ceilings the result when converting back. These functions are called by the pool at the edges of the swap path. Their choices matter because they can stack with the solver’s own truncation.

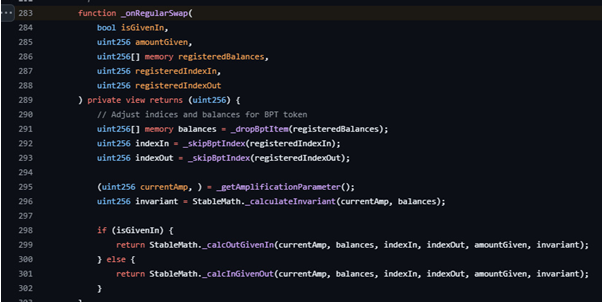

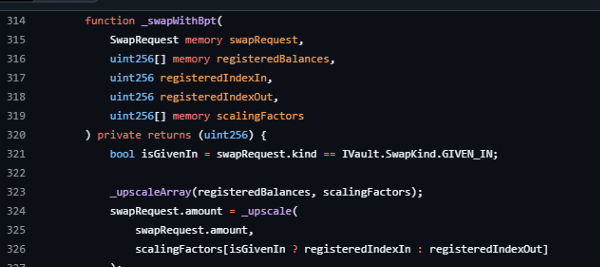

The pool logic that wires everything together is in ComposableStablePool.sol. The regular swap hook _onRegularSwap routes exact-in to StableMath._calcOutGivenIn and exact-out to StableMath._calcInGivenOut. This is where the code computes the invariant for the current balances and then calls into the stable solver. The BPT route _swapWithBpt explicitly upscales balances and the request amount, runs join or exit math, and then returns with _downscaleDown for exact-in and _downscaleUp for exact-out. That final step fixes the edge rounding applied to the value returned to the Vault.

Because StableMath._calcInGivenOut already adds one to the amount in, and _swapWithBpt ceilings when returning an input on exact-out, the path can be biased if earlier steps also floored amounts.

The base classes BaseGeneralPool and BasePool call the pool hooks and handle “upstream” work like refreshing rate-based scaling factors and applying fees. They prepare the registeredBalances and scalingFactors that the pool then converts with _upscaleArray. If those base steps deliver unscaled values that are immediately floored by _upscaleArray, that is the first source of truncation in the path. The pool then drops the BPT index from balances before calling the solver. That transformation changes which numbers feed the invariant, but it does not remove any truncation that has already happened.

Rate-provider code in PriceRateCache and ComposableStablePoolRates updates the scaling factors whenever a token has a changing rate. These modules do not create bias by themselves. They can change the magnitude of the truncated remainder because they alter scaling factors at the moment _upscaleArray runs. A small rate change right before scaling slightly shifts how much precision is lost to floor rounding.

The Vault’s batch-swap entry point composes many per-hop calls to onSwap. Each hop executes the same path described above. If each hop drops or adds a unit due to deterministic rounding, a long path of tiny hops can add up to an observable difference. The Vault does not introduce an opposite rounding step after the pool returns, so there is no natural cancellation at this layer.

From these components, the vulnerability mechanism is straightforward. A user amount is floored when upscaled to 18 decimals. The solver then executes several floor divisions and accepts an absolute one-unit tolerance. The swap calculator forces a final plus or minus one on the result. The pool returns values that are ceiled or floored at the edge. In an exact-out sequence, the input is pushed upward inside the solver and possibly again when downscaling. In an exact sequence, the output is pushed downward twice. A single small swap only shows a dust-level effect. A sequence of many small swaps, especially in one batch, converts that dust into value because the bias is deterministic and points the same way every time.

Exploitability depends on three conditions that are present in this code path. Exact-out swaps must be available because they require rounding the input up, and they use _calcInGivenOut, which adds one internally. The pool and Vault must allow many small hops to be chained. The math and scaling helpers must be the versions shown here that apply early floor rounding and fixed ±1 adjustments. No reentrancy or special tokens are needed.

Detection and Mitigation

Detecting the Exploit Early

Detecting this kind of bug requires watching the math, not just the money. Because the attacker didn’t steal through a single large transfer, but through thousands of small ones, normal alert systems missed it at first.

Here’s how such attacks can be detected earlier, in simple terms:

1. Watch for repeated micro-swaps.

- Most users trade in reasonable amounts. But an address making hundreds of tiny trades, especially in the same pool within seconds, is suspicious.

2. Monitor pool balance drift.

- Each Balancer pool has a hidden internal number called the invariant (D) that helps keep prices fair. When D changes too much after small trades, it suggests rounding or precision issues. Sudden or repeated “drifts” in D should raise an alert.

3. Track swap direction and timing.

- In normal use, swaps go both ways (buying and selling). In an exploit, most swaps happen in one direction only, designed to push the math bias repeatedly.

4. Use behavioral alerts instead of value alerts.

- Traditional systems track large losses. But this type of exploit needs detectors that track unusual patterns—many identical transactions, small trade sizes, and repetitive activity by the same wallet.

Mitigation: Steps to Prevent a Repeat

1. Upgrade to Balancer V3 (the safest option).

- The clearest fix is to move liquidity to Balancer V3 pools, which use an improved math library that handles rounding more safely. V3 has also added limits and better internal checks to prevent repeating the same tiny calculation errors.

2. Pause or retire vulnerable V2 pools.

- For operators still using Balancer V2, pausing affected pools immediately stops attackers from repeating the exploit. Over time, it’s safer to migrate all liquidity to the patched version.

3. Add transaction filters.

- Exchanges, aggregators, and front ends can protect users by blocking or warning against very small trades (for example, anything worth less than $1). These trades are often meaningless to real users but useful to attackers.

4. Introduce per-user rate limits.

- No normal user needs to make hundreds of trades in a single minute. Setting a limit for how many swaps one wallet can perform in a short time prevents mass rounding abuse.

5. Strengthen pool math with rounding-neutral logic.

- Future updates should ensure that rounding errors cancel out naturally rather than always rounding in one direction. Some DeFi protocols now use banker’s rounding (rounds up or down randomly or alternately) to prevent bias.

6. Improve testing for precision edge cases.

- Developers should test not just one large transaction but hundreds of small ones to see how the pool behaves after repetition. That’s how this bug could have been caught before it was exploited.

7. Regular invariant checks.

- Platforms should automatically recalculate each pool’s D value over time. If it drifts steadily without corresponding price changes, that pool can be flagged before a major loss happens.

Remediation and Recovery

Immediate Recovery Steps

When the exploit was discovered, Balancer’s first move was to contain the damage, not fix the math right away. In blockchain systems, once money is gone, it can’t be reversed, so the focus shifts to stopping the bleeding and protecting what’s left.

Here’s what remediation looked like in practical terms:

1. Pause the vulnerable pools.

- Balancer’s team immediately paused all V2 stable pools where possible. This prevented anyone (including attackers) from continuing to interact with the broken math logic.

2. Warn users and partners.

- Balancer posted public alerts, advising liquidity providers (LPs) to withdraw funds from any pool that used the same math contract. Aggregators, exchanges, and other DeFi apps connected to Balancer were also warned to disable affected pools on their platforms.

3. Trace and label attacker wallets.

- Blockchain security companies like PeckShield and Nansen helped trace the wallets used in the exploit. These wallet addresses were publicly labeled as “exploit addresses,” making it harder for attackers to move or cash out stolen tokens.

4. Secure unaffected pools.

- Balancer verified which pools were safe (non-stable pools, version 3 pools, and pools using different math code). These pools remained active to minimize disruption to the broader DeFi market.

5. Begin forensic analysis.

- A team of independent researchers reviewed transaction histories, pool formulas, and simulation results to confirm the root cause and rule out any other hidden bugs.

Long-Term Recovery

Once the situation was stable, the focus moved from reaction to repair, rebuilding user trust and ensuring the same mistake can’t happen again.

1. Encourage migration to Balancer V3.

- Liquidity providers were guided to move their assets to Balancer V3 pools, which use a new and safer math system. This version improves rounding accuracy and adds stronger invariant checks to prevent future drift.

2. Patch and audit the vulnerable code.

- The V2 stable-pool math library was corrected to handle rounding more carefully. The updated code was independently audited by multiple security firms before being redeployed.

3. Community discussion on reimbursements.

- While recovery in DeFi is difficult (since blockchain transactions can’t be reversed), Balancer governance began discussions about possible compensation for affected liquidity providers using insurance funds, treasury assets, or protocol fees.

4. Collaboration with exchanges.

- Centralized exchanges (CEXs) helped freeze or monitor addresses linked to the attacker. This prevented immediate liquidation of stolen assets and increased chances of partial recovery.

5. Launch of internal bug bounty expansion.

- Balancer expanded its bug bounty program, offering higher rewards for researchers who discover mathematical or precision-based vulnerabilities in pool logic.

Conclusion

The Balancer exploit was not a typical cyberattack; it was a mathematical oversight turned into a financial disaster. What looked like a harmless rounding choice inside the code ended up causing the loss of over $100 million across multiple chains.

It’s a reminder that in DeFi, precision matters. A single line of code that handles numbers incorrectly can open the door to large-scale exploitation. Unlike traditional systems, blockchain errors don’t stay hidden or recoverable; once value moves, it’s gone forever.

This event also highlights a deeper truth: security is not just about protecting access, it’s about protecting accuracy. Financial math on the blockchain must be treated with the same seriousness as encryption or key management.

Balancer’s quick action, pausing pools, investigating transparently, and encouraging migration to Balancer V3, helped contain the damage and restore trust. But the larger takeaway is for the entire DeFi industry:

● Never assume a number is “close enough.”

● Test not just once, but over thousands of repetitions.

● Build systems that can detect, alert, and self-pause when math behaves unexpectedly.

In simple words, this exploit showed how a few lost decimals became millions in real money. It’s a lesson that accuracy, no matter how small, is the true foundation of financial security on the blockchain.

References

Balancer Labs. (2019, September 19). Balancer whitepaper. Retrieved from https://docs.balancer.fi/whitepaper.pdf

Bitget / ChainFeeds. (2025, November 6). In-depth analysis of the Balancer V2 attack: Vulnerability mechanism, attack steps, and lessons learned. Retrieved from https://www.bitgetapp.com/news/detail/12560605050505

BlockSec Team. (2025, November 4). In-depth analysis: The Balancer V2 exploit. Medium. Retrieved from https://blocksecteam.medium.com/in-depth-analysis-the-balancer-v2-exploit-9552f6442437

Check Point Research. (2025, November 3). How an attacker drained $128 million from Balancer through rounding-error exploitation. Retrieved from https://research.checkpoint.com/2025/how-an-attacker-drained-128m-from-balancer-through-rounding-error-exploitation

CoinSpect. (2025, November 4). Balancer V2 stable pools exploit — Rate manipulation. Retrieved from https://www.coinspect.com/blog/balancer-rate-manipulation-exploit

Haney, S., Desfontaines, D., Hartman, L., Shrestha, R., & Hay, M. (2022, July). Precision-based attacks and interval refining: How to break, then fix, differential privacy on finite computers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.13793. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.13793

Rescana. (2025, November 4). Comprehensive analysis of the $128 million Balancer V2 DeFi exploit: Attack vectors, impact, and mitigation steps. Retrieved from https://www.rescana.com/post/comprehensive-analysis-of-the-128-million-balancer-v2-defi-e xploit-attack-vectors-impact-and-mit

Security Boulevard. (2025, November 7). Balancer hack analysis and guidance for the DeFi ecosystem. Retrieved from https://securityboulevard.com/2025/11/balancer-hack-analysis-and-guidance-for-the-defi-eco system

The Block. (2025, November 4–5). Balancer identifies rounding error as root cause of multi-chain DeFi exploit. TradingView News. Retrieved from https://www.tradingview.com/news/the_block%3A5d083e944094b%3A0-balancer-identifies-r ounding-error-as-root-cause-of-multi-chain-defi-exploit